Standards for Information Security Management

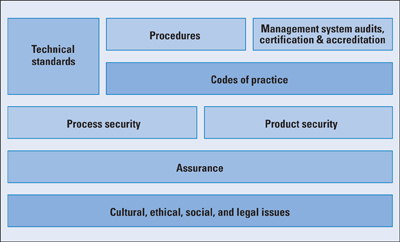

To effectively assess the security needs of an organization and to evaluate and choose various security products and policies, the manager responsible for security needs some systematic way of defining the requirements for security and characterizing the approaches to satisfy those requirements. This process is difficult enough in a centralized data processing environment; with the use of local- and wide-area networks (LANs and WANs, respectively), the problems are compounded. The challenges for management in providing information security are formidable. Even for relatively small organizations, information system assets are substantial, including databases and files related to personnel, company operation, financial matters, and so on. Typically, the information system environment is complex, including a variety of storage systems, servers, workstations, local networks, and Internet and other remote network connections. Managers face a range of threats always growing in sophistication and scope. And the range of consequences for security failures, both to the company and to individual managers, is substantial, including financial loss, civil liability, and even criminal liability. Standards for providing information system security become essential in such circumstances. Standards can define the scope of security functions and features needed, policies for managing information and human assets, criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of security measures, techniques for ongoing assessment of security and for the ongoing monitoring of security breaches, and procedures for dealing with security failures. Figure 1, based on [1], suggests the elements that, in an integrated fashion, constitute an effective approach to information security management. The focus of this approach is on two distinct aspects of providing information security: process and products. Process security looks at information security from the point of view of management policies, procedures, and controls. Product security focuses on technical aspects and is concerned with the use of certified products in the IT environment when possible. In Figure 1, the term technical standards refers to specifications that refer to aspects such as IT network security, digital signatures, access control, nonrepudiation, key management, and hash functions. Operational, management, and technical procedures encompass policies and practices that are defined and enforced by management. Examples include personnel screening policies, guidelines for classifying information, and procedures for assigning user IDs. Management system audits, certification, and accreditation deals with management policies and procedures for auditing and certifying information security products. Codes of practice refer to specific policy standards that define the roles and responsibilities of various employees in maintaining information security. Assurance deals with product and system testing and evaluation. Cultural, ethical, social, and legal issuers refer to human factors aspects related to information security. Many standards and guideline documents have been developed in recent years to aid management in the area of information security. The two most important are ISO 17799, which deals primarily with process security, and the Common Criteria, which deals primarily with product security. This article surveys these two standards, and examines some other important standards and guidelines as well. ISO 17799An increasingly popular standard for writing and implementing security policies is ISO 17799 "Code of Practice for Information Security Management." (ISO 17799 will eventually be reissued as ISO 27002 in the new ISO 27000 family of security standards). ISO 17799 is a comprehensive set of controls comprising best practices in information security. It is essentially an internationally recognized generic information security standard. Table 1 summarizes the area covered by this standard and indicates the objectives for each area. Table 1: ISO 17799 Areas and Objectives

With the increasing interest in security, ISO 17799 certification, provided by various accredited bodies, has been established as a goal for many corporations, government agencies, and other organizations around the world. ISO 17799 offers a convenient framework to help security policy writers structure their policies in accordance with an international standard. Much of the content of ISO 17799 deals with security controls, which are defined as practices, procedures, or mechanisms that may protect against a threat, reduce a vulnerability, limit the effect of an unwanted incident, detect unwanted incidents, and facilitate recovery. Some controls deal with security management, focusing on management actions to institute and maintain security policies. Other controls are operational; they address the correct implementation and use of security policies and standards, ensuring consistency in security operations and correcting identified operational deficiencies. These controls relate to mechanisms and procedures that are primarily implemented by people rather than systems. Finally, there are technical controls; they involve the correct use of hardware and software security capabilities in systems. These controls range from simple to complex measures that work together to secure critical and sensitive data, information, and IT systems functions. This concept of controls cuts across all the areas listed in Table 1. To give some idea of the scope of ISO 17799, we examine several of the security areas discussed in that document. Auditing is a key security management function that is addressed in multiple areas within the document. First, ISO 17799 lists key data items that should, when relevant, be included in an audit log:

It provides a useful set of guidelines for implementation of an auditing capability:

Under the area of communications and operations management, ISO 17799 includes network security management. One aspect of this management is concerned with network controls for networks owned and operated by the organization. The document provides implementation guidance for these in-house networks. An example of a control follows: Restoration procedures should be regularly checked and tested to ensure that they are effective and that they can be completed within the time allotted in the operational procedures for recovery. Similarly, the document provides guidance for security controls for network services provided by outside vendors. An example of guidance in this area follows: The ability of the network service provider to manage agreed-upon services in a secure way should be determined and regularly monitored, and the right to audit should be agreed upon. As can be seen, some ISO 17700 specifications are detailed and specific, whereas others are quite general. Common CriteriaThe Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation (CC) is a joint international effort by numerous national standards organizations and government agencies [3,4,5]. U.S. participation is by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the National Security Agency NSA). CC defines a set of IT requirements of known validity that can be used in establishing security requirements for prospective products and systems. The CC also defines the Protection Profile (PP) construct that allows prospective consumers or developers to create standardized sets of security requirements that will meet their needs. The aim of the CC specification is to provide greater confidence in the security of IT products as a result of formal actions taken during the process of developing, evaluating, and operating these products. In the development stage, the CC defines sets of IT requirements of known validity that can be used to establish the security requirements of prospective products and systems. Then the CC details how a specific product can be evaluated against these known requirements, to provide confirmation that it does indeed meet them, with an appropriate level of confidence. Lastly, when in operation the evolving IT environment may reveal new vulnerabilities or concerns. The CC details a process for responding to such changes, and possibly reevaluating the product. Following successful evaluation, a particular product may be listed as CC certified or validated by the appropriate national agency, such as NIST or NSA in the United States. That agency publishes lists of evaluated products, which are used by government and industry purchasers who need to use such products. The CC defines a common set of potential security requirements for use in evaluation. The term Target of Evaluation (TOE) refers to that part of the product or system that is subject to evaluation. The requirements fall into two categories:

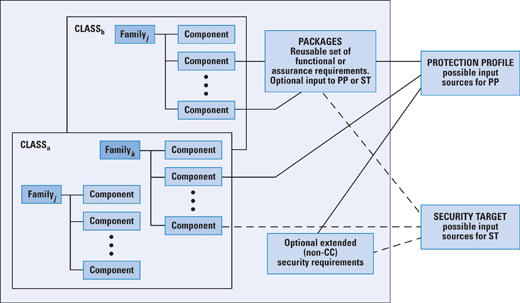

Both functional requirements and assurance requirements are organ-ized into classes: A class is a collection of requirements that share a common focus or intent. Each of these classes contains numerous families. The requirements within each family share security objectives but differ in emphasis or rigor. For example, the audit class contains six families dealing with various aspects of auditing (for example, audit data generation, audit analysis, and audit event storage). Each family, in turn, contains one or more components. A component describes a specific set of security requirements and is the smallest selectable set of security requirements for inclusion in the structures defined in the CC. For example, the cryptographic support class of functional re-quirements includes two families: cryptographic key management and cryptographic operation. The cryptographic key management family has four components, which are used to specify key generation algorithm and key size; key distribution method; key access method; and key destruction method. For each component, a standard may be referenced to define the requirement. Under the cryptographic operation family, there is a single component, which specifies an algorithm and key size based on a an assigned standard. Sets of functional and assurance components may be grouped to-gether into reusable packages, which are known to be useful in meeting identified objectives. An example of such a package would be functional components required for Discretionary Access Controls. The CC also defines two kinds of documents that can be generated using the CC-defined requirements.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between requirements on the one hand and profiles and targets on the other. For a PP, a user can select many components to define the requirements for the desired product. The user may also refer to predefined packages that assemble numerous requirements commonly grouped together within a product requirements document. Similarly, a vendor or designer can select numerous components and packages to define an ST. As an example for the use of the CC, consider the smart card. The protection profile for a smart card, developed by the Smart Card Security User Group, provides a simple example of a PP. This PP describes the IT security requirements for a smart card to be used in connection with sensitive applications, such as banking industry financial payment systems. The assurance level for this PP is Evaluation Assurance Level (EAL) 4, which is described subsequently. The PP lists threats that must be addressed by a product that claims to comply with this PP. The threats include the following:

Following a list of threats, the PP turns to a description of security objectives, which reflect the stated intent to counter identified threats or comply with any organizational security policies identified. Nineteen objectives are listed, including the following:

Security requirements are provided to thwart specific threats and to support specific policies under specific assumptions. The PP lists specific requirements in three general areas: TOE security functional requirements, TOE security assurance requirements, and security requirements for the IT environment. In the area of security functional requirements, the PP defines 42 requirements from the available classes of security functional requirements. For example, for security auditing, the PP stipulates what the system must audit; what information must be logged; what the rules are for monitoring, operating, and protecting the logs; and so on. Functional requirements are also listed from the other functional requirements classes, with specific details for the smart card operation. The PP defines 24 security assurance requirements from the available classes of security assurance requirements. These requirements were chosen to demonstrate:

The PP also lists Security Requirements of the IT Environment . They cover the following topics:

The final section of the PP (excluding appendices) is a lengthy rationale for all the selections and definitions in the PP. The PP is an industrywide effort designed to be realistic in its ability to be met by a variety of products with a variety of internal mechanisms and implementation approaches. The concept of Evaluation Assurance is a difficult one to define. Further, the degree of assurance required varies from one context and one function to another. To structure the need for assurance, the CC defines a scale for rating assurance consisting of seven EALs ranging from the least rigor and scope for assurance evidence (EAL 1) to the most (EAL 7). The levels are as follows:

The first four levels reflect various levels of commercial design practice. Only at the highest of these levels (EAL 4) is there a requirement for any source code analysis, and this analysis is required only for a portion of the code. The top three levels provide specific guidance for products developed using security specialists and security-specific design and engineering approaches. National Institute of Standards and TechnologyNIST has produced a large number of Federal Information Processing Standards Publications (FIPS PUBs) and special publications (SPs) that are enormously useful to security managers, designers, and implementers. Following are a few of the most significant and general. FIPS PUB 200 "Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems," is a standard that specifies minimum security requirements in 17 security-related areas with regard to protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of federal information systems and the information processed, stored, and transmitted by those systems[6]. NIST SP 800-100 "Information Security Handbook: A Guide for Managers," provides a broad overview of information security program elements to assist managers in understanding how to establish and implement an information security program [7]. Its topical coverage overlaps considerably with ISO 17799. Several other NIST publications are of general interest. SP 800-55 "Security Metrics Guide for Information Technology Systems," provides guidance on how an organization, through the use of metrics, identifies the adequacy of in-place security controls, policies, and procedures [8]. SP 800-27 "Engineering Principles for Information Technology Security (A Baseline for Achieving Security)," presents a list of system-level security principles to be considered in the design, development, and operation of an information system [9]. SP 800-53 "Recommended Security Controls for Federal Information Systems," lists management, operational, and technical safeguards or countermeasures prescribed for an information system to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the system and its information [10]. Other Standards and GuidelinesAnother important set of standards is the Control Objectives for Information and Related Technology (COBIT) [11], a business-oriented set of standards for guiding management in the sound use of information technology. It has been developed as a general standard for information technology security and control practices and includes a general framework for management, users, IS audit, and security practitioners. COBIT also has a process focus and a governance flavor; that is, management's need to control and measure IT is a focus point. COBIT was developed under the auspices of a professional organization, the Information Systems Audit and Control Association, (ISACA). The documents are quite detailed and provide a practical basis for not only defining security requirements but also implementing them and verifying compliance. Another excellent source of information is "The Standard of Good Practice for Information Security" from the Information Security Forum. The standard is designed as an aid to organizations in understanding and applying best practices for information security. Because it addresses security from a business perspective, The Standard appropriately recognizes the intersection between organizational factors and security factors. In addition to these standards, numerous informal guidelines are widely consulted by organizations in developing their own security policy. The CERT Coordination Center (www.cert.org) has an Evaluations and Practices section of its Website with a variety of documents and training aids related to information security for organizations. The Chief Information Officers Council (cio.gov) has published a collection of Best Practices and other documents related to organizational security. References[1] Eloff, J., and Eloff, M., "Information Security Management," Proceedings of SAICSIT 2003, South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists, 2003. [2] International Organization for Standardization, "ISO/IEC 27001 – Information technology – Security Techniques – Information security management systems – Requirements," June 2005. [3] Common Criteria Project Sponsoring Organisations, "Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation, Part 1: Introduction and General Model," CCIMB-2004-01-001, January 2004. [4] Common Criteria Project Sponsoring Organisations, "Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation, Part 2: Security Functional Requirements," CCIMB-2004-01-002, January 2004. [5] Common Criteria Project Sponsoring Organisations, "Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation, Part 3: Security Assurance Components," CCIMB-2006-09-003, September 2006. [6] National Institute of Standards and Technology, "Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems," FIPS PUB 200, March 2006. [7] National Institute of Standards and Technology, "Information Security Handbook: A Guide for Managers," NIST Special Publication 800-100, October 2006. [8] "Security Metrics Guide for Information Technology Systems," NIST Special Publication 800-55, July 2003. [9] National Institute of Standards and Technology, "Engineering Principles for Information Technology Security (A Baseline for Achieving Security)," NIST Special Publication 800-27, June 2004. [10] National Institute of Standards and Technology, "Recommended Security Controls for Federal Information Systems," NIST Special Publication 800-53, February 2005. [11] IT Governance Institute, "COBIT 4.0.," USA, 2005. [12] Information Security Forum, "The Standard of Good Practice for Information Security," 2005. WILLIAM STALLINGS is a consultant, lecturer, and author of more than a dozen books on data communications and computer networking. His latest book, with Lawrie Brown, is Computer Security: Principles and Practice (Prentice Hall, 2007). He maintains a computer science resource site for computer science students and professionals at WilliamStallings.com/StudentSupport.html and is on the editorial board of Cryptologia. He has a Ph.D. in computer science from M.I.T. He can be reached at ws@shore.net. |

||

|

|